| from Workers Hammer (September-October 1992) THE “QUIT INDIA” MOVEMENT 50 YEARS ON STALINIST ALLIANCE WITH CHURCHILL BETRAYED INDIAN REVOLUTION Part one of two “The Indian scene [in 1947] was heavy with menace, but one thing at least gave [British Labour prime minister Major Clement] Attlee great satisfaction. How gratifying it was, he noted, that an old Haileybury School boy like himself [Sir Cyril Radcliffe] was being sent out to take on the task of drawing a line through the [Punjabi] homelands of eighty-eight million human beings. “In India, Sikhs and Hindus prowled the cars of ambushed trains slaughtering every circumcised male they found. In Pakistan, Moslems raced along the trains they had stopped, murdering every male who was not circumcised.” --Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre, Freedom at Midnight Fifty years ago India’s struggle for independence from Britain entered its final, decisive phase. Commonly known as the “Quit India” movement after the main slogan put out by Mohandas Karamchand (“Mahatma” or “great soul”) Gandhi’s bourgeois Indian National Congress in August 1942, this phase swelled to a crescendo between 1945 and 1946. Soon after this, the subcontinent was arbitrarily partitioned into an 80 per cent Hindu-dominated India and an Islamic-confessional Pakistan; a horrendous communal blood-bath was unleashed. The movement’s denouement in February 1948 presented an appropriately bizarre neo-colonial spectacle: Britain’s last troops in India, the Somerset Light Infantry, disappeared marching westward through Bombay’s arched Gateway of India (where “King Emperor” George V had landed in 1911) to the strains of “God Save the King” and “Auld Lang Syne,” played in parting salute by an Indian Navy honour guard band of Sikhs and Gurkhas. Yet, at its tumultuous peak the mass upheaval, for a few crucial historic moments far outstripping the planned limits of its self-appointed minders and misleaders, had rocked the entire subcontinent, lifting it on to the very precipice of revolution. Millions of workers, soldiers, peasants, students and women, many flying Communist red flags alongside the Congress tricolour and the Muslim League’s green flag, defying British tank and machine-gun fire and even naval and aerial bombardment, jammed the streets and fields from Karachi to Calcutta. Cries of “Inquilab Zindabad!” [Long live revolution!] filled the air. Armed peasants started forcibly seizing land and setting up “soviets.” And in February 1946 a powerful strike by ratings (enlisted men) of the Royal Indian Navy in Bombay touched off an armed uprising by hundreds of thousands, including Royal Indian Air Force men, in that port and across the whole, electrified country, bringing it to a virtual standstill. Britain had lost control. Posed pointblank was not only India’s political independence from two hundred and fifty years of the British jackboot; the social liberation of India’s toiling masses from millennia of indigenous caste, gender, communal and class oppression was also now suddenly within grasp. What was needed was a revolutionary vanguard party of India’s small but strategic and modern, urbanised industrial working class which could rally and draw behind it the millions of peasant poor and other oppressed, oust the British, and put the native capitalist-landlord alliance out of business, launching a direct offensive for both national and social liberation through capturing proletarian state power. This policy, that of Permanent Revolution, had been the programme of Lenin and Trotsky’s Bolsheviks in the victorious October Revolution, thirty years earlier. That revolution had brought national and social liberation to the masses of backward Tsarist Russia, whose Tadzhik, Uzbek and other Central Asian peoples (just on the other side of the Himalayan Pamirs from northern Kashmir) had been catapulted from the seventh century into the twentieth as a result. In India the toiling masses had seen the Russian Revolution as a beacon of hope. Yet by midnight of 14 August 1947, when Congress prime minister Jawaharal Nehru rose to address “free” India’s parliament of capitalists, landlords and princes, the spectacular upsurge had been derailed. Instead, a pro-imperialist alliance of the Congress bourgeoisie and the Muslim League landlords had successfully diverted the revolutionary momentum into British imperialism’s waiting trap, the nightmare of communalist Partition. India’s working masses had paid with their lives--and were now about to pay even more--for the absence of a revolutionary party to lead its millions in an independent struggle for workers power. The new Muslim theocratic state of Pakistan (whose Punjabi-dominated west wing and Bengali east wing looked at each other across 1000 miles of hostile Hindu Indian territory) was carved out of the living bodies of thoroughly interpenetrated peoples, precipitating the biggest forced population transfers and one of the ghastliest communal slaughters in history. And in this crime, the Labour government of imperialist Britain and their bourgeois-landlord alliance of lackeys in the Congress and Muslim League were fully aided and abetted by the treacherous Stalinst trinity of the Kremlin, the Communist Party of Great Britain and the Communist Party of India. For in this historic betrayal, Stalin was the mover, the CPGB the enforcer and the CPI the executor on the spot. Lessons of the Chinese Revolution The developing militant wave and the advent of the World War II could have signaled the opening of great possibilities for a revolutionary party the size of the CPI. Instead the second imperialist war was to bring the nadir of Stalinist betrayal in India. To understand the CPI’s treachery on behalf of Churchill’s war effort it is necessary to take up the positions adopted by the Stalinised Comintern as against the Leninist tradition upheld by Trotsky and the Left Opposition. The Russian Revolution in 1917 fully confirmed Trotsky’s prognosis that “the complete victory of the democratic revolution in Russia is conceivable only in the form of the dictatorship of the proletariat, leaning on the peasantry. The dictatorship of the proletariat, which would inevitably place on the order of the day not only democratic but socialistic tasks as well, would at the same time give a powerful impetus to the international socialist revolution. Only the victory of the West could protect Russia from bourgeois restoration and assure it the possibility of rounding out the establishment of socialism” (“Three Concepts of the Russian Revolution”). Under the slogan of “socialism in one country” embraced by the conservative, nationalist Stalinist bureaucracy which had risen in the context of the isolated, war-weary and encircled Soviet workers state, the struggle for the extension of the revolution internationally was shelved in favour of “peaceful coexistence” with imperialism. This translated into defeat for the world proletariat and eventually transformed--after ruthless purges in most cases--the parties of the (Third) Communist International into tools of class-collaboration with their “own” bourgeoisies. In the colonial and neo-colonial world it meant rejecting the lessons of October and resuscitating the old Menshevik formula of “two-stage” revolution. As in China earlier, this was to have a devastating effect on the revolutionary proletariat of India. The tragedy of the Chinese Revolution of 1927-28 was a powerful negative confirmation of the permanent revolution, and it was over China that Trotsky extended his correct prognosis in Russia to all of the backward, colonial countries. The debate on China was whether or not to subordinate the Chinese workers and peasants to the native bourgeoisie in the form of Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang in which the CP was operating. When the Chinese CP proposed to leave the Kuomintang the plan was vetoed by the Comintern Executive on Stalin’s instruction. They were directed to hold down the class struggle against the “anti-imperialist” bourgeoisie in the cities and contain the peasant movement in the countryside. In early 1926 the Kuomintang itself was admitted to the International as an associate party. Only a few weeks later, on 20 March, Chiang carried out his first anti-communist coup, barring CP members in the Kuomintang. Under orders, the CP complied! After a challenge from the Left Opposition leaders Trotsky and Zinoviev and during the crucial days of the Shanghai insurrection which began in March 1927, Stalin stuck to the policy. The main task in China for the Communists was “the further development of the Kuomintang.” On 12 April the Kuomintang army carried out a massacre which cost the lives of tens of thousands of Communists and militant workers who had laid down their arms at Stalin’s orders. This was “socialism in one country” in practice! Congress--the Indian “Kuomintang”--and the CPI “India,” Trotsky had noted in May 1930, “is the classic colonial country as Britain is the classic metropolis. All the viciousness of the ruling classes and every form of oppression that capitalism has used against the backward people of the East is most completely and frightfully summed up in the history of the gigantic colony on which the British imperialists have settled themselves like leeches for the past century and a half” (“The Revolution in India, Its Tasks and Dangers,” Writings of Leon Trrotsky [1930]). Like pre-revolutionary Russia and China, the road to national liberation, agrarian reform, social equality and advancement lay in the programme of proletarian revolution, requiring a vanguard party defending the political independence of the working class. The weak national bourgeoisie, tied by a thousand threads to imperialism, could in no way carry out even the “democratic” tasks posed. The Indian industrial bourgeoisie, which started growing towards the very end of the 19th century and expanded considerably during World War I, was still no match for British industrial and finance capital. The Bolshevik-Leninist Party of India (BLPI--Indian section of the Trotskyist Fourth International) pointed out: “Despite the advance of Indian capital, British capital remains in effective monopolist domination in banking, commerce, exchange, insurance, shipping, in the tea, coffee and rubber plantations, and in the jute industry. In iron and steel, Indian capital has been forced to come to terms with British capital, and even in the cotton industry, the home of Indian capital, the control of British capital through the managing system is very great.”--BLPI Draft Programme Indian reality emphatically underlined the revolutionary correctness of the perspective of permanent revolution. The Indian Trotskyists drew the correct conclusion that “the Indian bourgeoisie, shackled as it is to Imperialism, cannot play the historical role of the West-European bourgeoisie in liberating and developing the productive forces. The industrial advance of India demands absolutely the overthrow of Imperialism, with which Indian bourgeois interests are indissolubly bound, and the overthrow of which they are bound to resist” (ibid). Faced with British imperialist intransigence, the weak and dependent Indian bourgeoisie sought methods of struggle that could pressure the colonial masters to make concessions without disturbing the social order by unleashing struggles of the masses that would threaten not just the British but also the Indian capitalists and their landlord brothers. The origins of Congress are instructive in this regard. An English ex-civil servant of the Empire, AO Hume, was a founder of the Indian National Congress in 1885. Its stated third aim was “THE CONSOLIDATION OF THE UNION BETWEEN ENGLAND AND INDIA, BY SECURING THE MODIFICATION OF SUCH OF ITS CONDITIONS AS MAY BE UNJUST OR INJURIOUS TO THE LATTER COUNTRY” (The Indian national movement, 1885-1947: Selected documents, ed. BN Pandey). As its first president, WC Bonnerjee explained: “Lord Dufferin... said there was no body of persons in this country who performed the functions which Her Majesty’s Opposition did in England... and as the English were necessarily ignorant of what was thought of them and their policy in native circles, it would be very desirable in the interests as well of the rulers as of the ruled that Indian politicians should meet yearly and point out to the Government in what respects the administration was defective and how it could be improved” (ibid). Enter Gandhi. At the time he arrived on the nationalist political scene at the start of World War I, Gandhi could be found enthusiastically urging London’s Indians to “think imperially” and organising a field Ambulance Training Corps as his personal contribution to the interimperialist war “effort.” Gandhi’s job was to extract as much as possible the British, in the common interests of saving capitalism, while keeping the burgeoning and now increasingly militant struggles of the workers and peasants at bay. The textile magnate Ambalal Sarabhai put it succinctly when he said Gandhi “was the best guarantee against communism which India possessed” (DA Low, Congress and the Raj). It was only after World War I that India’s modern proletariat, numbering five million by the second imperialist world war, emerged as a distinct force. The first great wave of strikes (1918-21) was triggered by mass immiseration under war conditions, a flu epidemic that killed 14 million, the Amritsar massacre in the wake of the draconian Rowlatt Act, and the impact of the 1917 Revolution. And it was the backdrop to Gandhi’s 1920-21 mass civil disobedience campaign for minimal constitutional reforms. The first six months of 1920 saw 200 strikes involving half a million workers, along with growing peasant struggles. Gandhi got cold feet, declaring that he had committed a “blunder of Himalayan proportions which had enabled ill-disposed persons, not true passive resisters at all, to perpetuate disorders.” In February 1922, on the eve of another passive resistance crawl, when 22 policemen were killed in the course of a peasant anti-rent agitation, Gandhi called off the entire non-cooperation movement, essentially going into purdah over the next decade. And the Congress told its supporters that withholding rent to the zemindars [landlords] was contrary to its policies and “the best interests of the country.” Gandhi re-emerged in the thirties when new waves of militant struggles broke out. He reiterated his opposition to “class war” and called for the “harmonious cooperation of labour and capital, the landlord and capital, the landlord and tenant.” The situation in India not only cried out for a revolutionary solution but provided great opportunities for building a communist-led movement against colonial oppression and to overthrow capitalism. The prestige of the October Revolution was immense among the toiling masses. Founded among other places in revolutionary Tashkent in 1920, the CPI had early succumbed to the global anti-revolutionary policies emanating from Stalin’s Comintern after 1924; Stalin’s search for “peaceful coexistence” did not help the Indian Communists. In the late twenties they employed themselves with generally rightist plans for front organisations and multi-class parties. Then the “Third Period” had them pursuing sterile sectarian policies which condemned the Indian nationalists equally with the British imperialists. In the popular front period (1935-39) they accepted the leadership of the Congress and “Gandhiji” as necessary for the first “democratic” stage of the revolution. And moreover, because Stalin was pursuing an alliance with “democratic” imperialist Britain, the CPI soft-pedaled the struggle against British imperialism, placing the emphasis on reforms and gradualist change. At the Seventh Congress of the Third International in Moscow in July-August 1935, the CPI was denounced for long-standing “left” sectarian errors and for using slogans such as “an Indian Workers’ and Peasants’ Soviet Republic,” and “confiscation of lands belonging to the zemindars (landlords) without compensation.” Even as late as March 1936 the Congress was characterised as “definitely a class organisation of the Indian bourgeoisie” in a CPI publication, but the new class-collaborationist line laid down by “India experts” for the CPGB, R Palme Dutt and Ben Bradley was: “The National Congress can play a great part and a foremost part in the work of realising the anti-imperialist People’s Front. It is even possible that the National Congress by the further transformation of its organisation and programme may become the form of realisation of the anti-imperialist People’s Front” (quoted in S Tagore, Against the Stream). The CPI supported the Congress in the provincial elections of 1937. In 1936 a miserable and tokenistic Congress proposal for agricultural reform was lauded. In fact the Congress ministries of this period did next to nothing to alleviate the condition of the peasantry. Indicatively the only places where Congress ministries even talked about land reform were in areas where the landlords were to a large extent Muslims and peasants Hindus, such as the United Provinces, Bihar and Madras. At the same time the inception of Congress ministries in some parts of India gave the CPI more room to organise, and with growing mass disillusionment with Congress the CPI began to grow significantly. It developed strong roots in the working class in major industrial cities like Bombay, and considerable influence in student and peasant organisations. But it held the struggles back in the interests of the alliance with Congress. In November 1938, after the shooting of workers protesting anti-trade-union legislation introduced by the Congress ministry in Bombay, one “Congress Communist” (CPI entrist in Congress) told a protest rally: “Anger and sorrow have been kindled in our minds by the oppression that has been perpetrated on the workers of Bombay. Still, we are proceeding with restraint with our eyes fixed on national solidarity and unity.” The CPI in World War II During the period of the Stalin-Hitler pact the CPI as all the other parties of the Comintern (which would be formally liquidated by Stalin in 1943) denounced the “democratic” facade of the British imperialists in their war against Germany. Indeed in contrast to the Stalinists of his Majesty’s CPGB who displayed visible discomfort at Stalin’s about face (with its pro-German tilt), many militants of the CPI appear to have relished the opportunity to take a full-blooded stance against their hated main enemy. In the context of mounting anti-imperialist militancy, this line would have come increasingly into contradiction with the CPI’s continuing adherence to the Stalinist policy of a “first” “democratic” stage in alliance with the bourgeois Congress, provoking splits and opportunities for revolutionary regroupment. But when Hitler’s “Operation Barbossa” was launched against the Soviet Union in June 1941 and the wartime alliance between Britain and the USSR was sealed, the Comintern instructed another sharp turn to the “People’s War Against Fascism” and all-out support for the war effort in the imperialist countries and their colonies. As late as July 1941 the CPI, lacking precise instructions from Stalin via the CPGB, however, had adopted a line which distinguished between the interimperialist war between the Allied and Axis powers and the need to defend the Soviet Union. A CPI manifesto issued at the time read in part: “The Communist Party declares that the only way in which the Indian people can help in the just war which the Soviet is waging, is by fighting all more vigorously for their own emancipation from the imperialist yoke. Our attitude towards the British Government and the imperialist war remains what it was.... We can render really effective aid to the Soviet Union, only as a free people. That is why our campaign for the demonstration our support and solidarity with the Soviet Union, must be coupled with the exposure of the imperialist hypocrisy of the Churchills and Roosevelts with the demand for the intensification of our struggle for independence” (quoted in David N Druhe, Soviet Russia and Indian Communism). But the CPI leadership, after the years of its popular front treachery, were not going to oppose Stalin’s dictates. They soon embraced the Allied war effort. In the “Guidelines of the History of the Communist Party of India,” by the Central Party Educational Department, the CPI noted the July position, adding: “Then a document proposing change of line was sent by the comrades in Deoli camp in December 1941. In February 1942 the PB said in a resolution: ‘Make the Indian people play a people’s role in the people’s war.’ In July 1942 the ban on the CPI was lifted and releases started. The main struggles were correct: ‘National government for national defence.’ ‘National unity for national government.’” Let’s be clear. The emissaries from the Comintern responsible for dealing with the CPI--the Communist party of Great Britain---broke the news to their Indian comrades that they were out of line. Harry Pollit’s letter announcing this was even deliberately permitted by the British authority to be passed to the Communists incarcerated in Deoli prison. Debate ensued and there were those who broke with the CPI rather than scab on the struggle against British imperialism for the sake of the “People’s War” but the CPI leaders accepted the new line. Their support to the war would now be “unqualified, wholehearted and full-throated.” For its part Congress’ formal position was that its support to the war was conditional on being granted independence from Britain. What this boiled down to was “demanding” some concessions in exchange for producing cannon fodder for the imperialist war effort. Then, emboldened by Britain’s difficulties as Japan advanced through the Pacific and into Burma and cognisant that they might soon need to deal with another imperialist overlord, Congress went from conditional support to open opposition, seeking to force a settlement with British imperialism. Even arch-reactionary Churchill was compelled to recognise that concessions were needed to shore up the shaky Raj. Sir Stafford Cripps, a “left” Labourite reputed to be sympathetic to the Indian national cause was dispatched to offer some meager and insulting divide-and-rule concessions. Even Gandhi called them “a post dated cheque on a bank that was failing.” Then as Charles Wesley Ervin related in his “Trotskyism in India: Origins through World War Two (1935-1945)”: ‘On 8 August 1942 Congress called for mass civil disobedience to pressurise the British to ‘quit India.’ The British panicked. Within twelve hours every important Congress leader was in jail or on his way. News of the arrests brought thousands onto the streets of Bombay.... The August Struggle had begun” (Revolutionary History Vol 1. No 4, Winter 1988-89). Arguing that Congress should form a temporary national government in collaboration with the Muslim League, the CPI bitterly opposed the “Quit India” resolution and in the ensuing struggles denounced Congress for its “sabotage.” Even in its mendacious retrospective, the CPI’s “Guidelines” admit: “It adopted an antistruggle antistrike line. A line of avoiding [!] mass struggles was worked out on the plea that they would damage the war effort or help profascist elements to sabotage it, eg. CC plenum reports, articles in weekly People's War. Quit India movement was opposed on the same basis [as] the Forward Bloc [Subhas Chandra Bose’s split] and socialists who attacked communists as ‘British agents’ were denounced in retaliation as fifth column and fascist agents.” The newly formed BPLI plunged into the August events. Key cadre came from exiled Ceylonese Trotskyist who had escaped arrest and imprisonment in Ceylon, after the British crackdown on their party for its revolutionary defeatist stance on the imperialist war and their organising of militant struggles among the strategic Tamil plantation workers. As the heroic Trotskyists argued in their Bombay leaflet the very day the historic “August Action” began: ”The slogans of ‘Abolition of Landlordism without Compensation’ and ‘Cancellation of Peasant Debt’ must be leading slogans of the struggle. Not only no-tax campaigns against the government, but also no-rent campaigns against all landlords, must be commenced on the widest possible scale, leading to the seizure of land by the peasants through Peasants’ Committees. “Manning the nerve centres of the economy, the workers are in the position to deal the most devastating blows against imperialism.... A mass general political strike against British imperialism will paralyse and bring to a stop the whole carefully built up machinery of imperialist administration. “The Indian soldiers, who are peasants in uniform, cannot fail to be affected by the agrarian struggle against landlordism and imperialism.” Many BLPI militants were imprisoned in the immediate aftermath. The British were not the only ones out to crush them, either; the CPI press “viciously slandered the Trotskyists as ‘criminals and gangsters who help the Fascists’ by allegedly calling for ‘strikes, sabotage, food riots and all forms of anarchy’ and ‘attempting to stir up trouble in all war industries’.... Stalinists from Ceylon were brought over to India to hunt for Samasamajists [Ceylonese Trotskyists], and CPI stool-pigeons fingered militants to the police during the war” (Ervin, ibid). The BLPI’s draft programme made an eloquent exposition of Leninist tactics in the second imperialist war: “With the mass slaughter, the unparalleled destruction and untold sufferings entailed by the war, the international proletariat and the oppressed masses of the colonies are being driven to the point where they will see in revolution the only way out. ‘The chief enemy of the people is in its own country.’ The prime task of proletarian revolutionaries in the present imperialist conflict is to follow the policy of revolutionary defeatism in relation to their ‘own’ government and to help develop the class struggle to the point of civil war regardless of the possibility of such a course leading to the defeat of one’s ‘own’ government.... “International developments are governed by two main contradictions. The first is the contradiction of the existence of a workers’ state (the Soviet Union) in a capitalist world. The second is the inter-imperialist rivalry which has now broken openly into war.... But the supercession of the capitalist-workers’ state antagonism and the temporary postponement of a united capitalist war of intervention against the Soviet Union by no means removed the danger of an attack on the Soviet Union by one of the parties in the inter-imperialist embroilment.... “But the parties of the Fourth International, while defending the Soviet Union from imperialist attack, do not for a single moment give up the struggle against the Stalinist apparatus. Incapable of carrying out the real defence of the Soviet Union, the Stalinist bureaucracy seeks the aid not of the international proletariat, but exclusively of Anglo-American Imperialism.... The workers’ state will be able to emerge victorious from the holocaust of war only under one condition, and that is, if it is assisted by the revolution in the West or in the East.” Thus the BLPI stood out as a revolutionary pole during the Second World War. Despite its exemplary work, programmatic soundness and significant local successes, the small and overwhelmingly clandestine forces of the BLPI were insufficient to take advantage of the revolutionary crisis. The Congress leaders feared the unleashing of the workers and peasants against the capitalists and landlords many times more than they desired to enforce the demand to “Quit India” on the British imperialists; the Stalinists with their groveling before Churchill had made themselves for a key period of time “the most universally detested political organisation in India.” The intervention of a revolutionary Trotskyist party with some real weight in the proletariat was at this juncture the decisive element in whether the question of India was solved along the October model or left after post-war “independence” to the bloody partition designed by the British imperialists. During this period of subordination to Churchill and in line with the British divide-and-rule stratagems, the CPI flirted with the feudalist, British-backed Muslim League. It even decided there was a Muslim “nation” and adopted for some time the project of Pakistan. Later, they would shift back to fawning blandishments to Gandhi’s Congress. We will take up in greater detail these and other concrete examples of their perfidy and how Stalinist betrayal helped pave the way for the “solution” of the Churchills, Mountbattens and Cripps in the second and concluding part of this article. |

|

| Stalin: gravedigger of revolution (Workers Hammer caption) |

|

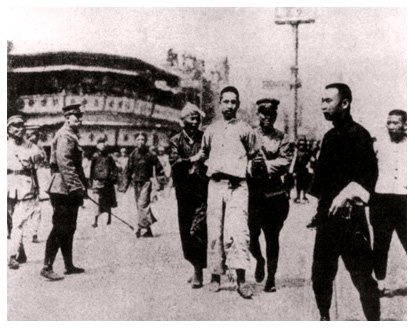

| Communists and workers rounded up and killed by the Kuomintang in Shanghai, 1927. |