THE “QUIT INDIA” MOVEMENT 50 YEARS ON

STALINIST ALLIANCE WITH CHURCHILL BETRAYED INDIAN REVOLUTION

Part two

In their efforts to crush the Indian independence struggle and radical social struggle, imperialist Britain, Churchill’s wartime coalition and Attlee’s Labour government alike, and the bourgeois-landlord lackeys in the Congress and Muslim League were fully aided and abetted by the treacherous Stalinist trinity of the Kremlin, the Communist Party of Great Britain and the Communist Party of India. The first part of the article (see Workers Hammer no 131, September/October) concluded:

“During this period of subordination to Churchill and in line with the British divide-and-rule stratagems, the CPI flirted with the feudalist, British-backed Muslim League. It even decided there was a Muslim ‘nation’ and adopted for some time the project of Pakistan. Later, they would shift back to fawning blandishments to Gandhi’s Congress. We will take up in greater detail these and other concrete examples of their perfidy and how Stalinist betrayal helped pave the way for the “solution” of the Churchills, Mountbattens and Cripps in the second and concluding part of this article."

Before turning to the CPI’s own contribution to the horrors of the Partition, it is worth reviewing the line of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) on India during World War II, not least because the CPGB were the agency for enforcing the subordination of the struggle for independence to Churchill’s war in its “mentor” role to the Indian Communists.

Having enlisted enthusiastically in the “People’s War” the Communist Parties not only insisted on “sacrifices” (ie, no strike pledges, cessation of social struggle) from the working classes within the “democratic” imperialist countries but also from the colonial slaves of those imperialisms. Thus, when resistance to British rule broke out in India, the British Stalinists (as well as the CPI) denounced the struggle as playing “into the hands of the Axis powers” (Black, Stalinism in Britain). CPGB leader Harry Pollitt wrote to Churchill with the following advice: “our [!] paramount aim must be to win the willing co-operation of the Indian nation in the common struggle against Fascism.” At its Congress in 1944 the CPGB emphatically rejected independence before the war ended, instructing the Indian masses that: “Establishment of a representative Indian National Government as an ally of the United Nations during the war, and freedom for the Indian people to choose their own form of Government after the war” was the order of the day. Black’s description of these Stalinists as the “Empire builders of the British ‘Communist’ Party” is apt.

The Bolshevik-Leninist Party of India, revolutionary Trotskyists, described the situation in India during the war:

“British imperialism has instituted a system of repressive legislation, progressively inaugurating a gendarme regime not less systematic and ruthless than that of Russian czarism or German fascism. Since the commencement of the imperialist war, repression has been many times intensified. Even those nominal rights previously possessed by the masses have been openly withdrawn, and a naked rule of terror substituted through the Defense of India Act.... The press has been gagged by a series of iniquitous Press Acts and a systematic police censorship of all publications. Rights of free speech and assembly have been so curtailed that they are practically non-existent. Radical and revolutionary political parties are compelled to lead an underground existence.

“The right to strike no longer exists in all ‘essential war industries’.... Thousands of militant mass leaders have been imprisoned on flimsy pretexts or detained without trial. The restriction of individual movement by means of externment and internment orders has become a commonplace...” (quoted by Henry Judd, India in Revolt).

By contrast the ban on the CPI was lifted by a grateful British Raj in 1942 and a government circular of 20 September 1943 praised the CPI as “almost the only Party which fought for victory.” A CPI self-criticism produced years later is damning enough about what is meant:

“It adopted an antistruggle line. A line of avoiding mass struggles was worked out on the plea that they would damage the war effort or help profascist elements to sabotage it, eg. CC plenum reports, articles in People's War. The Quit India movement was opposed, on the same basis the Forward Bloc and socialists who attacked communists as ‘British agents’ were denounced in retaliation as fifth column and fascist agents. In B. T. Ranadive’s report to the first congress on ‘Working Class and National Defence’ it was stated that production being ‘a sacred trust’ and ‘conditional support of production a left nationalist deviation’ therefore ‘strikes should be firmly prevented.’”

In addition to its self-confessed “antistruggle” line during the war, the CPI as well played straight into the hands of British imperialism’s schemes to consciously promote communalist divisions.

CPI and Britain’s “Divide and Rule”

From the outset, Indian nationalism was “a theme scored with religious, class, caste, and regional variations” (Wolpert, A New History of India), which given its social origins, was dominantly Hindu and upper-caste-based and frequently openly reactionary. A prime example was the early Congress “Extremist” leader BG Tilak, who first made his mark when he opposed the token reformist 1891 “Age of consent” Bill (raising the age of statutory rape of child brides from ten to twelve) under the war cry “Religion in danger!” Gandhi alienated vast numbers of Muslims with his explicitly Hindu-myth and scripture-based rhetoric, describing his utopia as Ram Rajya (“the kingdom of Ram”--the Hindu epic hero-god). Such themes are the basis for subsequent fascistic Hindu chauvinism, such as the BJP/RSS combine today. In the absence of a communist leadership consciously able to transcend and combat it by bringing the revolutionary proletarian, anticommunal, integrated class axis decisively to bear on the events leading up to 1947, this poison was bound to skewer any possibility of a progressive solution to India’s complex internal problems.

Far from communalism being an “eternal” feature of the Indian landscape, as the racist imperialist apologists would have it, it was the British who, through their systematic backing of one community against another to subjugate both, consciously nurtured this phenomenon as well as other caste, religious and national differences. Following the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny (significantly sparked by the refusal by Muslim and upper-caste Hindu sepoys [soldiers] alike to bite a new cartridge coated with animal fat) which far exceeded the bounds of the initial triggering episodes and revealed the depth of anti-British anger in the country, Governor General Elphinstone urged, “Our endeavor should be to uphold in full force the (for us) fortunate separation which exists between the different religions and races: not to endeavor to amalgamate them” (Henry Judd, India in Revolt). From this to the creation of separate Hindu and Muslim electorates in 1905-6 and thence to a series of other notorious “Communal Awards” culminating in the Partition: the imperialist logic of “divide-and-rule” was clear.

The novel Tamas no doubt truly portrays the efforts of CPI militants in the Punjab to fight the communalist slaughter during the Partition, but that blood-bath was prepared both by the CPI’s general support to the bourgeois nationalists and its particular wartime policies with respect to the Muslim question. One aspect of the Cripps’s Mission proposals in 1942 was a concession aimed at the Muslim League that areas could “opt out.” Given that Jinnah’s Muslim League had pledged “benevolent neutrality” in the imperialist war and the importance of recruitment from Muslim Punjabis, Pathans and Baluchis for the British Army, this was a crucial divide-and-rule attempt to uphold the British war effort. The CPI, in its Central Party Education Department’s Guidelines of the History of thCommunist Party of India (1974) admits the “serious mistake our party made on the question of Pakistan”:

“With the antistruggle line referred to above went the right-opportunist approach to the question of Congress-League (or national) unity, logically culminating in our support to Pakistan and the akali demand for Sikh homeland. Failure to build up enough pressure on British imperialists and to build unity from below led to helpless reliance on unity from above. ‘Destiny of the nation depends on national unity--Congress-League unity’ which with Jinnah adamant on his demand for Pakistan led to trailing behind the Muslim League in order to bring Gandhi-Jinnah together.”

The CPI went from denouncing the Muslim League as reactionary and communalist (which it was) to generally giving it more favourable coverage than Congress. Muslim League General Secretary Liaquat Ali Khan for example praised the CPI for its “ceaseless efforts to convince the Hindu of the justice of the demand for the rights of the self-determination to Muslims.” And CPI leader Joshi argued in August 1944 for strong and independent Muslim states in the north-west and north-east. Additionally late 1944 the CPI argued for separate electorates for Untouchables, exactly in line with British imperialist “divide-and-rule” manoeuvers at that time.

The CPI’s flirtation with the Muslim League and Pakistan was not some healthy attempt to grapple with the complexities of the national question as some apologists have suggested, but a direct product of the alliance with Churchill and their efforts to cement that alliance. After all the Muslim League was also opposed to the “Quit India” struggles. And when the CPI “corrected” its flirtation with the feudalist Muslim League it was only to swing back to bourgeois Congress, policies that led directly to the CPI and CPI(M)’s refusal today to defend legitimate national struggles such as those of the Kashmiris and the Sikhs.

In the service of tailing Congress, CPI leader PC Joshi reached new depths of Stalinist prostration before the leader of India’s Kuomintang. At the time of Gandhi’s release from prison in 19944, Joshi declared:

“Gandhiji, the beloved leader of the greatest patriotic organisation of our people, the mighty Indian National Congress is back in our midst again.... Every son and daughter of India, every patriotic organisation of our land, is looking to the greatest son of our nation to take it out of the bog in which none is safe.”

Amidst this record of sordid betrayal, acknowledged by the Stalinists’ own self-criticisms, about the only thing left for them to point to in that period is the relief work that the CPI organised during the Bengal famine. That famine in 1943 was a direct result of the imperialist war: wartime inflation, grain speculation and hoarding exacerbated by the loss of grain from Burma led to mass starvation. The arrogant indifference of the colonial administration was compounded by Churchill’s decision to cut back shipping to India. AJP Taylor noted, “A million and a half Indians died of starvation for the sake of a white man’s quarrel in North Africa” (English History 1924-1945).

The CPI’s famine relief work was not part of some revolutionary agitation against the war, but linked closely to its “war effort” on the food production “front.” Even if it did assist many in dire straits, the CPI’s famine relief work was a variant of Salvation Army mission work for Winston Churchill. In Bengal the CPI lost cadre because of its flirtation with the Muslim League, and it is noteworthy that in areas where the CPI dominated the peasant associations such as eastern Bengal and Telangana the peasant struggles over land and usury were restrained during the war compared to other areas.

The situation in Bengal impinges directly on the question of Subhas Chandra Bose and the Indian National Army (INA). There are Stalinoid critics of Gandhi’s Congress (and thus presumably its CPI tails) who took to Bose’s INA as a revolutionary alternative. At one time a left critic within Congress and elected as its head over the objections of Gandhi et al, Bose split to form the Forward Bloc Party in Bengal. Forward Bloc was banned and Bose arrested in 1940; he escaped on the eve of his trial in 1941 and traveled across northern India to Afghanistan, from there to Moscow. During the pre-June Russo-German alliance, Bose was welcomed by Hitler and “given high-powered radio facilities to beam daily broadcasts to India... urging his countrymen to rise in revolt against British tyranny” (Wolpert). In the spring of 1943, Bose traveled to Southeast Asia whereupon Tojo turned over all his Indian POWs to Bose’s command. In January 1944 he started his Indian National Army on their march north crossing the borders of India and reached the outskirts of Tripura’s state capital, Imphal, by May. Defeated by the British garrison, the INA surrendered in Ragoon and Bose escaped on the last Japanese plane to leave Saigon. He died in Formosa after a crash landing. When the captured officers of Bose’s INA went on trial in the winter of 1945-6 they were widely heralded as nationalist martyrs. On 18 February 1946 the Royal Indian Navy mutinied in Bombay harbour; the mutiny spread to Karachi. The British stepped up their attempts to extricate themselves from India.

Undoubtedly the INA was popular, particularly in Bengal, and among its ranks were those seeking a way to fight British imperialism rather than “turning the other cheek” ŕ la Gandhi. However the paeans offered to Bose in, for example, a feature article in the 4 August Asian Times as achieving “a signal victory” and providing “the last nail in the coffin of British rule in India” miss the point that larger world events had intervene and in fact Bose had subordinated himself to the Axis powers who were Britain’s imperialist rivals during the war. Where the CPI bowed before Churchill, the INA functioned at the behest of and under the protection of the Japanese imperialists. As the Japanese forces scored victories in rapid succession at Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore and Burma the possibility of a Japanese invasion and victory in India was strongly felt. Bose had thrown his lot in with another would-be colonial conqueror. The INA fought in Burma--just as Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang fought on the other side with American imperialism. Both the Kuomintang and the INA subordinated the national struggle to their respective imperialist overlords. In China and in Southeast Asia the colonial masses very quickly learnt that the Japanese masters were no better than their deeply hated English, American, Dutch and French masters. The tragedy in India, and especially Bengal, was that the masses were given no choice but subordination to one or another imperialist.

These betrayals in India expose those such as the Stalinists of the Lalkar publication of the Indian Workers Association who absurdly insist that “revisionism” began with Krushchev’s reign. For them, “So long as Comrade Stalin was in the leadership of the CPSU and was organising the tireless vigilance that needed to be exercised” “trounc[ing]” “the reactionary Trotskyite and Bukharinite opposition” all was well! (In fact, the CPI(M) still celebrates Stalin’s birthday in Calcutta.) And the Stalinists today prefer not to talk too much about their record in India during the Second World War, not only because it is such an affront to the revolutionary aspirations of the masses but also because they continue to pursue a class-collaborationist alliance with the Indian bourgeoisie.

Instead they seek to hide behind the figure of Stalin as a great war leader who defeated fascist barbarism. Somehow the Stalinist sins in India are to be exonerated on the basis that Stalin saved mankind. To this end, Lalkar's Harpal Brar turgidly regurgitates all the old Stalinist lies about Tukhachevsky being an agent of Hitler to justify his murder and the purge of the Red Army officer corps in his book Perestroika: The Complete Collapse of Revisionism. In the course of these bloody purges--between 1937 and 1939 (ie beginning during the popular front period)--the Red Army lost three of its five Marshals, all eleven of its Deputy Commisars for Defence, 75 of 80 of its members of the Military soviet, all its military district commanders who held that post in June 1937. The naval and air chiefs of staff were killed. Thirteen out of 15 army commanders were shot, 57 out of 85 corps commanders were shot, as were 110 out of the 195 divisional commanders. In the Far Eastern forces, over 80 per cent of the staff were purged. Tukhachevsky had predicted an attack like Operation Barbarossa and he and his comrades had a lively sense of technological innovation. These experienced and talented veterans of the Civil War were replaced by incompetent cronies of Stalin, who abolished the Red Army’s tank units--one of these replacements thought automatic weapons were just for policemen.

Right up to the day of the invasion Stalin was shipping vital raw materials to Germany. Warnings and precise intelligence from Trepper’s Red Orchestra and Richard Sorge in Japan were labeled as “English provocations” and not passed on to the general staff. Stalin forbade the dispersal of the air force (and it was consequently massacred on the ground) and ruled out any effective planning of defence in depth. Even after the invasion had begun, Stalin countermanded orders for the artillery to return fire, and forbade air-raid precautions in cities under attack. The criminal conduct of Stalin and his gang directly led to the loss of two and a half million soldiers in 1941, huge areas of territory (including important industrial plants which Stalin had refused to locate east of the Volga until that summer) and an almost fatal blow being delivered to the workers state.

The Soviet Union survived because despite Stalin the Red Army fought tooth and nail to stop the onslaught. In December 1941 Zhukov’s effective counterattack was wrecked by Stalin’s personal meddling and as late as the summer of 1942 the simple incompetence of Stalin and one of his toadies led to the loss of 200,000 men in the Crimea. It was only with the emergence of a competent layer of generals not liable to listen so much to Stalin that the heroism of the Red Army and Soviet peoples was turned into the liberation of the Soviet homeland and Eastern Europe from the Nazi scourge. Not only did Stalin’s general policies of “socialism in one country” lead to near fatal catastrophe but his particular military contribution was disastrous.

For a revolutionary proletarian solution!

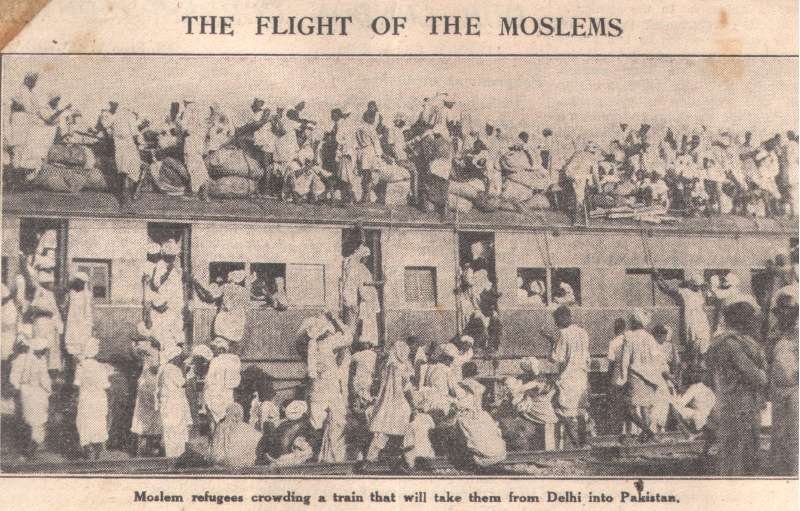

At independence the subcontinent faced the unspeakable horrors of Partition and today it remains one of the most impoverished, oppressed and exploited areas of the world, a veritable prison-house for national minorities, women and lower castes. The communalist slaughters engulfing Partition killed between one and two million Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus (mainly in Punjab and Bengal) and the forced migrations in its aftermath displaced over eleven million. A New York Times correspondent, Robert Trumbull, reported of the Partition: “In India today blood flows oftener than rain falls. I have seen dead by the hundreds and, worst of all, thousands of Indians without eyes, feet or hands. Death by shooting is merciful and uncommon” (quoted in Collins and Lapierre, Freedom at Midnight). Muslim babies were discovered “roasted like piglets on spits” and the 45-mile road from Lahore to Amritsar became such an “open graveyard” that, according to one British officer, “The vultures had become so bloated by their feasts they could no longer fly.” A stationmaster at Amritsar recounted what had initially seemed to be a “phantom train,” one of many rolling into Punjabi stations at the time: “The floor of the compartment before him was mass of human bodies, throats cut, skulls smashes, bodies eviscerated. Arms, legs, trunks of bodies were strewn along the corridors of compartments.... He turned to look back at the train. As he did, he saw in great white-washed letters on the flank of the last car the [Pakistani] Moslem assassins’ calling card. ‘This train is our Independence gift to [Indian Congress nationalists] Nehru and Patel’” (ibid).

The lessons of the struggle for Indian independence and the social liberation of India’s toiling masses are crucial not only for revolutionaries on the subcontinent but in all those countries where the permanent revolution applies, from South Africa to Iran. A Leninist-Trotskyist party must be built in irreconcilable struggle against every kind of nationalism and popular frontism, counterposing a revolutionary programme for the emancipation and reconstruction of the oppressed under the dictatorship of the proletariat. Writing in 1915 of the tasks for Russian revolutionaries Leon Trotsky called for “a revolutionary workers' government, the conquest of power by the Russian proletariat”:

“But revolution is first and foremost a question of power--not of the state form (constituent assembly, republic, united states) but of the social content of the government. The demands for a constituent assembly and the confiscation of land under present conditions lose all direct revolutionary significance without the readiness of the proletariat to fight for the conquest of power....” (“The Struggle for Power”)

Because the Bolsheviks were committed to such a programme, the Russian revolution of 1917 produced the first workers state on the planet. The USSR stood then as a beacon for the colonial and semi-colonial masses struggling for their liberation, as well as for the exploited working masses in the imperialist countries. Lenin and Trotsky’s Third International, later to be destroyed by Stalin, sought to bring the lessons of October to the workers of every land.

Today we in the International Communist League (Fourth Internationalist) fight to forge a revolutionary international which Lenin and Trotsky would recognise as their own. It will be an especially gratifying victory when the workers of the entire Indian subcontinent lead all the oppressed in throwing off the chains of neocolonial enslavement through victorious revolution.

back to Part one

back to index

An Open Letter to the Workers of India by Leon Trotsky

To the Workers and Peasants of India: Manifesto of the Fourth International (1942)

for more on the BLPI, see Trotskyism in India (Part One): Origins Through World War Two (1939-45) by Charles Wesley Ervin

The Trotskyist Press on India (1939-51) for writings by the BLPI and contemporaneous articles in British and American Trotskyist publications

email anti-caste

anti-caste home